Tabs Issue 70: Super! Really enjoyed it!

Lynn sent me the first YouTube video I ever watched, and it was a Borat clip. This was the time in the summer and fall of 2006 when we discovered the character and when yelling “my wiiife” and saying “is nice” was fresh and novel and would make me laugh until I cried. It was so new, so unused. A couple of years later, when all humor had been trampled out of this phrase, my brother’s friend, who I’d always looked up to, said it, and that was when I knew I was now definitely cooler than he was.

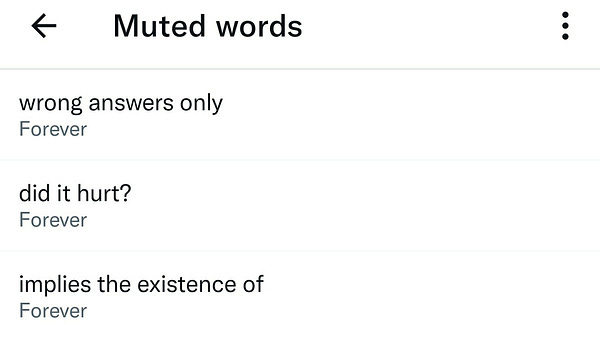

Such is the fate of so many jokes: to flourish briefly until all the humor is consumed, depleted, flattened into nothing. By the time a corporate Twitter account or BuzzFeed are using the joke or the formulation, it is like a tube of toothpaste that can be contorted no further. The humor’s been all squeezed out.

The speed at which this occurs on Twitter is sometimes demoralizing. The window of time in which to reach “greater and greater heights of rhetoric and answerback and improvisation,” as Patricia Lockwood writes in No One Is Talking About This, is short. The fun of the internet is watching the “elastic and snappable verbal play” in action: the days when you can watch an image or a phrase multiply, iterate, reflect back on itself, ever more distorted and clever, are engrossing. These are the “arms full of the sapphires of the instant” that Lockwood cherishes.

Inevitably, though, it is used one time, or several thousand times, too many. Unfortunately, the speed with which something goes from being fresh to being trite is so fast that it feels like we have no time to revel in it! These “anointed” words, as Lockwood calls them, become internet poisoned very quickly, such that the only way to use these terms without feeling like an idiot is to use them ironically. In time everything calcifies. Consider this clip of Gigi Hadid talking about Emma Chamberlain at the Met Gala this year (ignore the caption):

Can we agree that “major” and “slay” are dead, now that two women speaking with barely any affect use these formerly vibrant terms to describe utterly unremarkable style choices? Can we announce time of death on drag culture jargon now, please.

Much the same thing has happened to the language of mental health. So many concrete concepts have had their power stripped from them by hysterical and incorrect use. So many truly useful terms have gone the way of “live love laugh.”

This cycle makes our language more exhausted and exhausting.

It is, of course, inevitable to rely on standard formulations when we speak. There’s a reason we resent autocomplete and Gmail autoreplies : they highlight how predictable the way we speak is. My goal as an English teacher is for my students to sound like Gmail autoreplies. It would be the ultimate proof of fluency. The objective is to recognize a situation and know the appropriate response: when you agree to a plan, you say, “sounds good,” without actually thinking about or through the words we’re using. The less you think before you speak, the more native you are. That’s the relief you experience when you switch from a foreign language to your mother tongue: the mindlessness, the unnecessariness of figuring out how to speak in the most mundane situations, the frictionlessness of the transition from the thought to its expression. It is a vacation.

There is something ironic about the fact that language and its infinite creativity, which is one of the metrics by which humans are differentiated from animals, is largely used in absolutely uncreative ways. It’s ok! We cannot spend our days thinking of the most original ways to express ourselves. That’s why when you hear “lives rent free in my head” for the first time, it’s so tantalizing: a new image to describe the same old thing. It takes effort to find the words that most accurately convey our feelings, especially because we often don’t take the time to figure out what exactly those thoughts are. That’s why we rely on words like “interesting,” which is a word that ultimately says nothing at all. (Trying to avoid using it is a difficult exercise.)

Consider also the emotional inflation to which Americans are prone (I say Americans because any time a French person imitates an American, all they do is say “great!” “amazing!”). In an interview, Doreen St. Felix, discussing how TV shows are talked about, says,

[There is] the distance, the gap—or maybe it’s bigger than a gap—between what we actually feel, our emotions, the messiness of them, the grayness of them, and how we vocalize them […] Anyone who says that a show is the best show they’ve ever seen doesn’t actually believe that. That’s just their way of communicating whatever emotion the show gave them, whether it was pleasure or they were aroused by it.

These inflated terms are not meant literally and your interlocutors know that. But then what is meant? Shouldn’t we make the effort to express the “grayness” of our emotions instead of relying on shortcuts that flatten so much into small talk? Small talk in the sense that nothing is said or that nuance is not allowed. (This excellent essay has a really great discussion about how it has become impossible to say “not all men”: “Generalizing harshly and broadly but implying ‘you know which ones I mean’ is an intellectual and rhetorical laziness.”)

And what happens when you actually watch the best show you’ve ever seen? As Louis CK said,

As humans [again, this is an American trait] , we waste the shit out of our words. It’s sad. We use words like “awesome” and “wonderful” like they’re candy. It was awesome? Really? It inspired awe? It was wonderful? Are you serious? It was full of wonder? You use the word “amazing” to describe a goddamn sandwich at Wendy’s. What’s going to happen on your wedding day, or when your first child is born? How will you describe it? You already wasted “amazing” on a fucking sandwich.

I will end on this anecdote from a New York Times essay, which perfectly illustrates Louis CK’s point:

In the Apollo years, NASA sent military test pilots into space, not poets or preachers; they came back in possession of extraordinary knowledge that, by dint of personality or professional inclination, they seemed helpless to communicate. As the Gemini and Apollo astronaut Michael Collins once put it, “It was not within our ken to share emotions or to utter extraneous information.” Asked what it was like to go to the moon, Apollo 12’s Pete Conrad replied: “Super! Really enjoyed it!”