Last week, we had our bimonthly salon, where we get together and one person does a presentation about a subject they doesn’t know much about but that they’ve researched for us. The topic was the birth and golden age of animation, which saw the creation of such characters as Mickey Mouse, Betty Boop, and Popeye. As part of the presentation, Roberto showed us Humorous Phases of Funny Faces, the first animated cartoon, from 1906.

It starts with a hand drawing a man’s face. Then the hand disappears as a woman’s face is sketched out by a now-invisible hand. After that, the faces become animated as the drawings become characters that interact. Then, at 1:23, the hand reappears and erases them, a moment that’s surprisingly jarring. The artificiality of the movement is thrown into immediate relief: these are just lifeless drawings, still. It only took 20 seconds to believe in the illusion. It was probably immediate, really, and only the reintroduction of the hand highlights how instantaneous the suspension of disbelief is.

It reminds me of a talk I once went to where Ed Park brought up the Magritte painting La Condition Humaine and pointed out that while the viewer automatically considers the landscape more real than the painting on the easel depicting the landscape, both of them are equally unreal.

The viewer may ask, and indeed, one viewer did ask, if there is something hiding behind the painting on the easel. To which Magritte responded, “Behind the paint of the painting there is the canvas. Behind the canvas there is a wall. Behind the wall there is… etc. Visible things always hide other visible things. But a visible image hides nothing.”

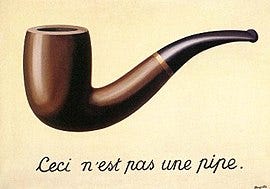

The same logic applies to the Treachery of Images: Magritte forces us to confront that we conflate the image of a pipe with the actual pipe.

It’s a very clever sleight of hand, though there’s no trick to it. We’re the ones tricking ourselves, easily forgetting that it is all representation. It’s inevitable: we believe our own eyes, even when we know better than to do so. People compare themselves to images on Instagram knowing that they’re filtered and photoshopped. In one great South Park episode, Wendy, to prove to the boys that anyone can look hot on Instagram, photoshops a picture of Lisa, a girl everyone considers ugly, which the boys then take for her true appearance. Wendy’s lesson backfires completely.

A painted image may hide nothing, but a photographic image excels at occlusion precisely because it lays a more credible claim to faithful representation. We are wired to believe our eyes! It’s an act of willpower not to. The brain must overpower the eyes, an act that is at time difficult. (Really, though, the brain does it constantly when it filters out our nose, which our eyes actually perceive all the time.)

Most of the time, our eyes and our brain act in concert as the brain augments the information the eyes provide. Given that we operate on associations and patterns, no AR necessary! We already have it. It’s a cornerstone of advertising: show one thing and let the associations with a lifestyle or an ideology do the rest or brands can just straight up instrumentalize political polarization (see: Black Rifle Coffee). Between video conferencing and social media we are constantly either using objects to display our values or being subject to targeted advertising that knows just which values match which products. This brings me to two recent articles. First there’s Lithub “Inside the Picture Perfect—and Highly Lucrative—Business of Book Styling”, about people who buy books as decor and apparently keep book shops alive, a valid but depressing argument.

These carefully curated shelves are often the handy work of a professional designer or book stager who will select titles for you. More often than not, these books come across as props intended to be on camera—acting as signifiers much like a Birkin bag or an expensive watch. While those items can indicate a certain level of status and wealth, an artfully staged bookcase aims to convey something as well, although perhaps more subtly.

Then there’s “Welcome to the Shoppy Shop” by Emily Sundberg, in which she describes all the fine food shops that sell the same DTC brands that populate our Instagram feeds. Those aesthetics are very appealing to me and to many of my cohort and the very design of the packaging is shorthand for a loose association of values like green, organic, not mass-produced, left-wing, somehow, even though the brands don’t necessarily explicitly state that at all. The consumer is the one attributing these qualities as suggested by the colors and shape of the label and the container. Kyle Chayka comments, “We know these minimalist-ish generic aesthetics are not connected to any true local origin, but we see them as indicative of some kind of authenticity.” (In fact all these fine foods shops and stores of their ilk order from the same wholesale website. Nothing niche about it.)

What are we meant to do? We can’t go to visit the chicken farm ourselves! We have to just trust the label.

The extreme case of this conflation of packaging with some set of values is Great Jones, an Instagram-famous company making pastel-colored cookware. After a falling out between the co-founders, the full-time staff quit, and yet the company had the best quarter of its existence. Albert Burneko wrote a great article about this in 2021, in which he concluded:

The absolute most generous true description you can apply to Great Jones is that it conducts arbitrage on cheap pastel-colored cookware with flimsy enamel cladding, made by other companies with less robust brands. But the truest thing you can say is that Great Jones, like so many other companies, is a skimming operation: It launders somebody else’s actual manufacture through its own aggressive branding, and takes a cut of the proceeds. The company can have the best quarter of its existence despite having no full-time employees, despite having literally no capacity to do anything other than exist as a legal fiction, because it never actually did anything. Anything! It never did anything.1

In a separate article on the same scandal, Chayka wrote that the millenial aesthetic will end when “customers learn that a compelling narrative is not the same thing as the integrity of a product or of the business selling it.” That means seeing the label and, as Magritte advised, recognizing that behind the label is some glue, behind the glue is a bottle, in the bottle is a product which can offer nothing but itself.

This whole thing reminds me of the conclusion of Barbarians at the Gate, an account of the convoluted twists and turns of the battle to take RJR Nabisco private in the ‘80s, born seemingly of the CEO’s boredom with running a very successful business. It is all about various bankers guided in their decisions to move billions of dollars by their egos and slights they’d previously felt from their colleagues. In any case, at the end of it all, the authors imagine the founder of Reynolds tobacco and Nabisco walking through the wrekage: “They would turn to one another, occasionally, to ask puzzled questions. Why did these people care so much about what came out of their computers and so little about what came out of their factories? Why were they so intent on breaking up instead of building up? And last: What did this all have to do with business?”

I'm going to be honest, I had a really hard time focusing on the second half of this essay because I was suddenly so aware of my nose 😅